Uber Technologies is offering data from trips on its ride-hailing platform to city officials, planners and policymakers to help them better understand traffic patterns and improve investments in infrastructure.

The move will likely win Uber goodwill with city officials, even as the company has resisted other bids for data by some cities. New York, for example, wants to collect trip records from vehicles on hire to monitor adherence to driver fatigue regulations, which Uber has rejected citing individual privacy issues.

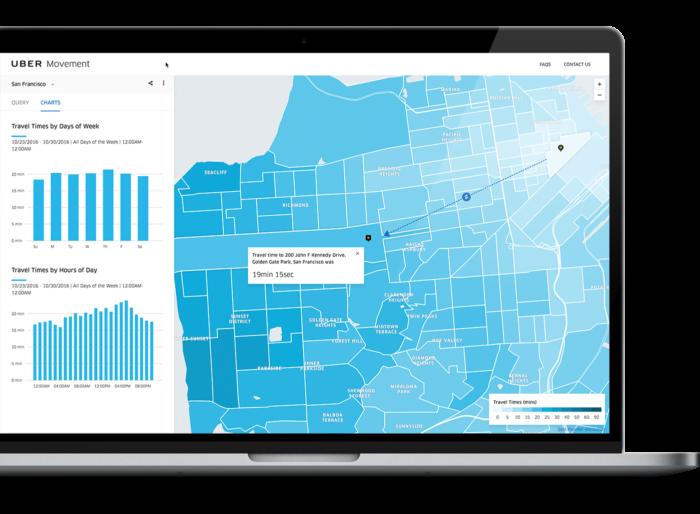

Some of the data collected by Uber over 2 billion trips across 450 cities will be provided under the new program, called Movement. However, the data will be “anonymized and aggregated into the same types of geographic zones that transportation planners use to evaluate which parts of cities need expanded infrastructure, like Census Tracts and Traffic Analysis Zones (TAZs),” Jordan Gilbertson, Uber’s product manager and Andrew Salzberg, head of transportation policy, wrote in a blog post Sunday.

Other ride-hailing companies have also offered data to planners. Cooperation with city planners could ensure that the ride-hailing concept gets more firmly entrenched in urban transport planning.

Easy Taxi, which started operations in Latin America, Grab in Southeast Asia and French operator Le.Taxi in December joined a partnership with the World Bank and other organizations to make traffic data derived from their drivers’ GPS streams available under an open data license.

Uber has set up a website for providing the information. Access to the data on the website will be on invitation initially, though the company promises to make it available freely to the public soon. The insights on the Movement website are available under the Creative Commons, Attribution Non-Commercial license, which would restrict the use of the data for commercial purposes.

“Since Uber is available 24/7, we can compare travel conditions across different times of day, days of the week, or months of the year—and how travel times are impacted by big events, road closures or other things happening in a city,” the executives wrote.

The concept of sharing aggregated data with cities is already being tried by Uber in Australia, where it has tied with Infrastructure Partnerships Australia to measure the performance of transport systems. Data from Uber was also used to analyse the impact of the Metrorail outage in Washington, D.C., on March 16 last year on congestion citywide during the evening commute hours, and was used to analyze travel conditions during the 2015 holiday season in Manila.

Uber’s provision of data to local authorities is likely to come under close scrutiny by consumer groups who have in the past complained about the company’s collection of user data. In December last year, the company said it would collect location data “from the time you request a trip until . . . up to five minutes after the driver ends a trip, even if the Uber app is in the background.” Users can, however, opt out from the monitoring.

In a privacy policy change from July 2015, the company said it would be tracking the location of its users’ devices even when they are not using its service and the app is running in the background.