One of the biggest challenges the U.S. economy faces in 2017 is expected appreciation in the dollar, which, as everyone knows, will crush the many American companies that survive selling products overseas.

Not so fast.

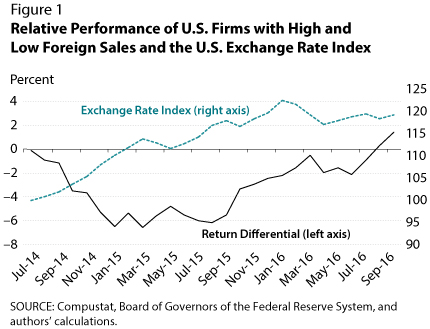

It turns out that a major piece of conventional wisdom on Wall Street may not be so clear-cut after all. The St. Louis Fed, studying the issue of how high-export firms fare against low-export firms in times of U.S currency gains, found that while the former group gets hit in the short term, the effect has tended to go away as time goes by.

Looking at the period of July 2014 to September 2016, the Fed study by economists YiLi Chien and Paul Morris discovered that the period through about September 2015 saw stock market outperformance by firms that derive less than half their sales from overseas, but that flipped thereafter to the point where companies that had a majority of sales overseas started to take the lead over the past summer.

During that period, the dollar index, which measures the greenback against six competitors around the world, rose more than 20 percent. Back in November it broke the 100 mark, meaning it trades at better than par against its peers, for just the second time in more than a decade.

MANUFACTURERS HIT HARDER

The stock market managed to make it through. The S&P 500 rose 8.4 percent through the period — unspectacular and below trend, to be sure, but still higher — and economic growth continued to muddle along much the same as it has throughout the recovery.

Companies survive a higher dollar by using a number of strategies: They shift production and marketing, enter longer-term trade agreements and hedge currency exposure. As the St. Louis Fed put it in the paper:

One possible explanation pertains to the global supply chain. Firms with high foreign sales are larger and tend to be multinational. In today’s global market, it is likely that they are capable of adjusting their production and sales between home and foreign countries. The adjustment could be costly and slow and, hence, not feasible in the short term. In the long term, firms could shift production and possibly focus more on the domestic market to reduce the impact on profits caused by the dollar’s appreciation.

In fact, in the time frame the Fed examined, the percentage of sales to foreign countries for S&P 500 companies declined, from 47.8 percent in 2014 to 44.3 percent in 2015, according to Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Of course, the period also saw an earnings recession. But that also has turned around, with the index expected to show its second consecutive annualized growth rate in the fourth quarter.

The pattern of U.S. companies bouncing back from initial periods of dollar appreciation likely will get tested again. Many market pros figure the greenback to keep rising under aggressive fiscal policies from President-elect Donald Trump and the Fed’s slow but steady pattern of interest rate hikes ahead.

The toughest burden could come for manufacturing firms.

In that sector, the pressure of a rising currency on manufacturers with more than half their sales foreign “is stronger and persisted longer.” But even in that case, the differential between the two types of manufacturing firms narrowed through time and was just 2 percent in the third quarter of 2016.

“Data show that the recent appreciation of the dollar starting in 2014 lowered the value of firms only in the short run,” the Fed economists said. “By August 2016, the value of firms with high foreign sales recovered or even surpassed the value of those with low foreign sales. This empirical result indicates that, in the long run, U.S. firms can adjust quite well in response to a large and sharp exchange rate fluctuation.

source”cnbc”