In Indonesia, rising backlash against a local politician may provide terror organisation Islamic State a fresh opportunity to deepen its grip on Southeast Asia’s largest economy.

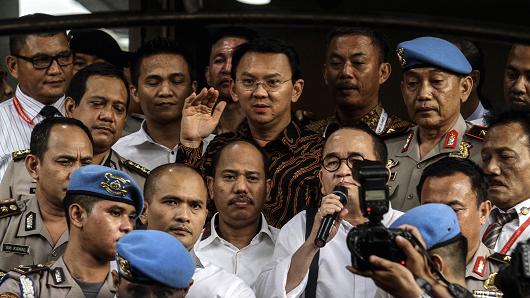

The nation’s capital city is facing gubernatorial election in February and current Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, commonly known as Ahok, is running to keep his seat. The 50-year old was promoted from deputy governor to governor after his predecessor Joko Widodo won the 2014 presidential election. If elected next year, Ahok—a Christian of Chinese ethnicity—would become Jakarta’s first elected non-Muslim governor in a country with the world’s largest Muslim population.

However, Ahok’s election campaign has antagonized the country’s conservative base, with some religious groups preaching that Muslims shouldn’t vote for “non-believers.”

Anti-Ahok sentiment is now at a boiling point after the politician cited a Koranic verse during a September 27 speech. The religious verse suggests Muslims should not take Jews or Christian as their allies or leaders and in his remarks, Ahok said Indonesians should not be deceived by his opponents who use the verse to influence the election.

The Indonesia Ulema Council (MUI), a circle of the religious elite, insists that he committed blasphemy by insulting the Muslim holy book. But the governor has apologized and said he never meant to offend the religion.

Still, the public has pounced on Ahok. 10,000 demonstrators took to Jakarta’s streets last month and as many as 50,000 people protested last Friday, demanding that the governor be prosecuted for alleged hate speech.

Implications

The rallies won’t dent Ahok’s chances of victory next year because of the bulk of the Jakarta electorate maintains a more liberal stance, Eurasia’s Indonesia analyst Achmad Sukarsono said in a recent note.

The bigger concern is what the protests mean for fundamentalism in Indonesia after Islamic State (IS) fighters publicly supported Friday’s protest via social media.

“The issue has gone beyond elections to become a rallying cry for Islamists pushing for Islamization,” Sukarsono explained. “With Ahok in the race, these rallies will continue through the campaign period, with a risk of Islamic State supporters seeking to leverage them for their own gains.”

The country’s national police chief Tito Karnavian has also warned that sympathizers of the international network are likely to “take advantage” of the volatile environment.

“Over Telegram and other messaging services, they [IS supporters] have been encouraging each other to use the November 4 rally to fan the flames of jihad across the country,” Sidney Jones, director of the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, wrote in a recent note published on think tank The Lowy Institute’s website.

Last week, a 22-year old IS follower stabbed several police officers and was found to be carrying a pipe bomb—the latest in Indonesia’s IS-linked attacks that began in January when four militants launched an attack in downtown Jakarta. “IS supporters have specifically urged each other to emulate this young man, whose bravery was cited in IS bulletin Al-Naba,” Jones stated.

Social media has long been the terror vehicle’s preferred means for boosting its international membership base, but IS is increasingly working on the ground with local militant cells in countries such as Indonesia.

“IS is also using other mechanisms to exploit the situation by networking with and influencing diverse parties to join IS and its affiliated groups in Indonesia,” said Rohan Gunaratna, head of the International Center for Political Violence and Terrorism Research at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

Since the Arab Spring, the bloc—also called the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria—has exploited protests and demonstrations to expand its support base, he added.

President Jokowi, who postponed a state visit to Australia on Saturday as a result of the unrest, has called for national calm but critics say he must do more to crack down aggressively on this issue.

“IS will succeed if government is not proactive and bold,” Gunaratna cautioned.

By letting the anti-Ahok hated build for more than a month, the government was also ignoring the constitution, Jones flagged.

“If the MUI’s arguments were to be accepted by the state, it would be a rejection of the compromise worked out in 1945 between secular nationalists and Muslim leaders that obliged Indonesians to believe in one God but dropped a phrase requiring Muslims to follow Islamic law.”

source”gsmarena”